Tradeoffs in dispersal and persistence in variable environments

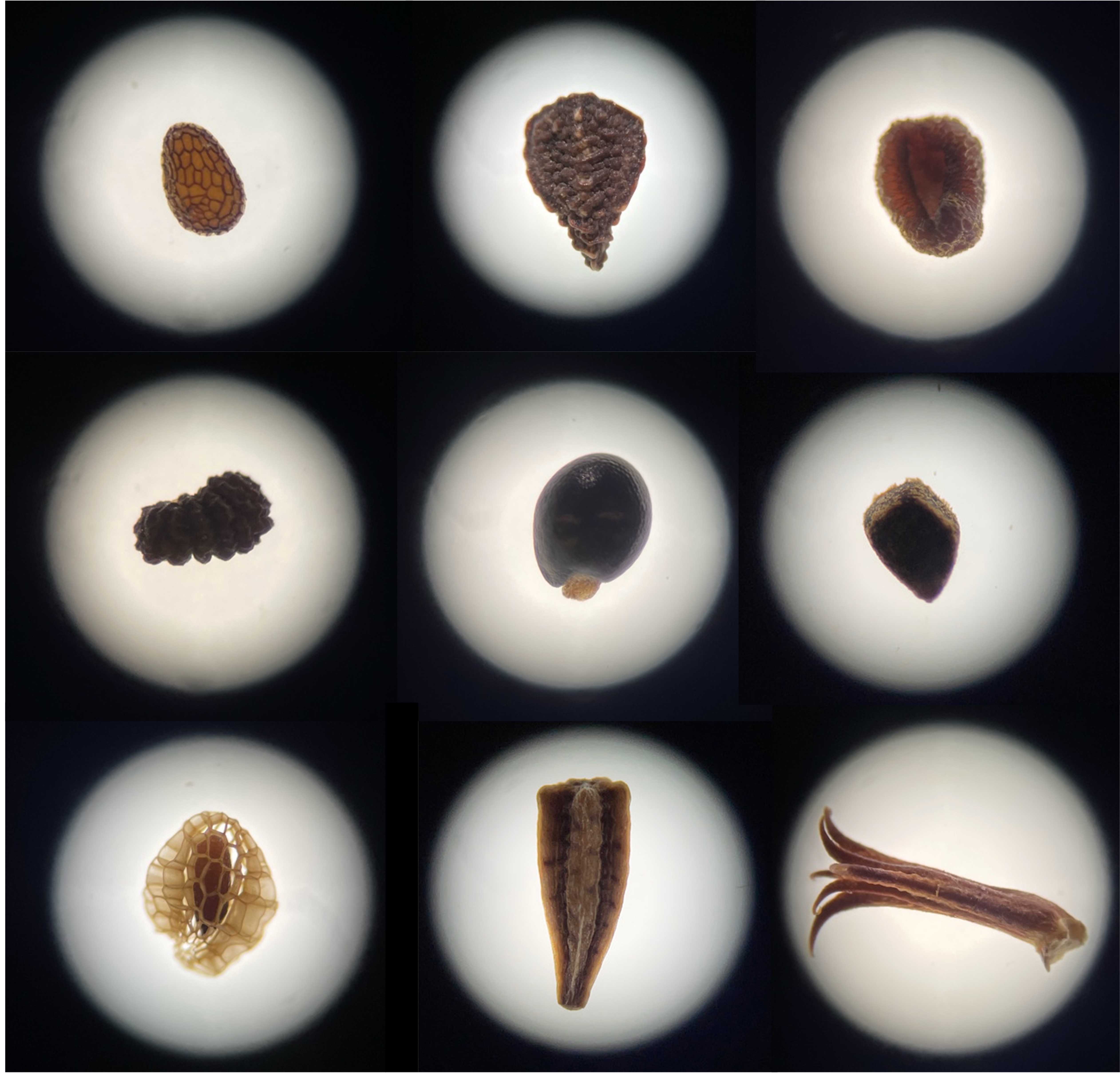

Despite the importance of early life stages in plants, we know very little about controls over seed persistence and dispersal, two seed functions that are predicted to tradeoff, but with mixed empirical support. These functions are particularly important in dryland systems where many species rely on seed banks to buffer their populations during unfavorable periods, which will become more frequent under climate change. My postdoc project with Dr. Lauren Hallett at the University of Oregon and Dr. Jennifer Gremer at the University of California, Davis utilizes biological seed collections housed in botanical gardens to conduct a largescale seed trait study on dryland annual species across an aridity gradient. To then link these traits with dispersal and persistence behavior, I am collaborating with Dr. Pierre-Olivier Cheptou at the Center for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology in Montpellier, France to build models that can predict abundance in the “hidden” seedbank from aboveground plant community data. I will be applying these findings towards understanding invasibility of California rangelands and the future of seedbanks in annual desert communities.